Home / Training / Manuals / Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners’ manual / Chapter 9: Inflammatory lesions of the uterine cervix

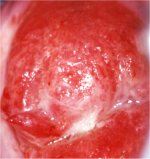

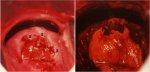

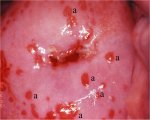

figure 9.1: Reddish “angry-looking...

figure 9.1: Reddish “angry-looking...

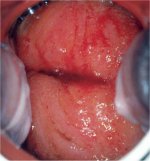

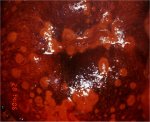

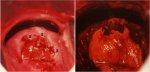

figure 9.2: Chronic cervicitis: th...

figure 9.2: Chronic cervicitis: th... figure 9.3: Chronic cervicitis: th...

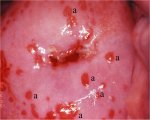

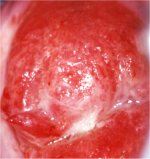

figure 9.3: Chronic cervicitis: th... figure 9.4: Multiple red spots (a)...

figure 9.4: Multiple red spots (a)... figure 9.5: Colposcopic appearance...

figure 9.5: Colposcopic appearance...

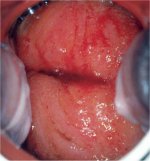

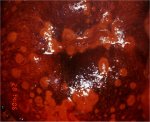

figure 9.6: Stippled appearance (a...

figure 9.6: Stippled appearance (a... figure 9.7: Trichomonas vaginalis ...

figure 9.7: Trichomonas vaginalis ... figure 9.8: Chronic cervicitis: th...

figure 9.8: Chronic cervicitis: th...

Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners’ manual, Edited by J.W. Sellors and R. Sankaranarayanan

Chapter 9: Inflammatory lesions of the uterine cervix

Filter by language: English / Français / Español / Portugues / 中文- The inflammatory lesions of cervical and vaginal mucosa are associated with excessive, malodorous or non-odourous, frothy or non-frothy, grey or greenish-yellow or white discharge and symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, back ache, pruritus, itching, and dyspareunia.

- Colposcopic features of cervical inflammation such as inflammatory punctation, congestion and ulceration as well as ill-defined, patchy acetowhitening are widely and diffusely distributed in the cervix and vagina and not restricted to the transformation zone.

Inflammatory lesions of the cervix and vagina are commonly observed, and particularly in women living in tropical developing countries. Cervical inflammation is mostly due to infection (usually mixed or polymicrobial); other causes include foreign bodies (an intrauterine device, a retained tampon, etc.), trauma, and chemical irritants such as gels or creams. The clinical features and diagnostic characteristics of these lesions are described in this chapter to help in the differential diagnosis of cervical lesions.

The inflammatory lesions are associated with mucopurulent, seropurulent, white or serous discharge and symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, backache, pruritus, itching and dyspareunia. As stated earlier, they are most commonly caused by infections or irritating foreign bodies. Common infectious organisms responsible for such lesions include protozoan infections with Trichomonas vaginalis; fungal infections such as Candida albicans; overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria (Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Gardnerella vaginalis, Gardnerella mobiluncus) in a condition such as bacterial vaginosis; other bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Haemophilus ducreyi, Mycoplasma hominis, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, and Neisseria gonorrhoea; and infections with viruses such as herpes simplex virus.

Women with cervical inflammation suffer every day with pruritic or non-pruritic, purulent or non-purulent, malodorous or non-odorous discharge, frothy or non-frothy discharge, which stain their underclothes, necessitating regular use of sanitary pads. These inflammatory conditions are thus symptomatic and should be identified, differentiated from cervical neoplasia, and treated. A biopsy should be taken whenever in doubt.

Examination of the external anogenitalia, vagina and cervix for vesicles, shallow ulcers and button-like ulcers and the inguinal region for inflamed and/or enlarged lymph nodes, and lower abdominal and bimanual palpation for pelvic tenderness and mass should be part of the clinical examination to rule out infective conditions.

The inflammatory lesions are associated with mucopurulent, seropurulent, white or serous discharge and symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, backache, pruritus, itching and dyspareunia. As stated earlier, they are most commonly caused by infections or irritating foreign bodies. Common infectious organisms responsible for such lesions include protozoan infections with Trichomonas vaginalis; fungal infections such as Candida albicans; overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria (Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Gardnerella vaginalis, Gardnerella mobiluncus) in a condition such as bacterial vaginosis; other bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Haemophilus ducreyi, Mycoplasma hominis, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, and Neisseria gonorrhoea; and infections with viruses such as herpes simplex virus.

Women with cervical inflammation suffer every day with pruritic or non-pruritic, purulent or non-purulent, malodorous or non-odorous discharge, frothy or non-frothy discharge, which stain their underclothes, necessitating regular use of sanitary pads. These inflammatory conditions are thus symptomatic and should be identified, differentiated from cervical neoplasia, and treated. A biopsy should be taken whenever in doubt.

Examination of the external anogenitalia, vagina and cervix for vesicles, shallow ulcers and button-like ulcers and the inguinal region for inflamed and/or enlarged lymph nodes, and lower abdominal and bimanual palpation for pelvic tenderness and mass should be part of the clinical examination to rule out infective conditions.

Cervicovaginitis

The term cervicovaginitis refers to inflammation of the squamous epithelium of the vagina and cervix. In cervicovaginitis, the cervical and vaginal mucosa respond to infection with an inflammatory reaction that is characterized by damage to surface cells. This damage leads to desquamation and ulceration, which cause a reduction in the epithelial thickness due to loss of superficial and part of the intermediate layers of cells (which contain glycogen). In the deeper layers, the cells are swollen with infiltration of neutrophils in the intercellular space. The surface of the epithelium is covered by cellular debris and inflammatory mucopurulent secretions. The underlying connective tissue is congested with dilatation of the superficial vessels and with enlarged and dilated stromal papillae.

Cervicitis

Cervicitis is the term used to denote the inflammation involving the columnar epithelium of the cervix. It results in congestion of underlying connective tissue, desquamation of cells and ulceration with mucopurulent discharge. If the inflammation persists, the villous structures become flattened, and the grape-like appearance is lost and the mucosa may secrete less mucus.

In both the above conditions, after repeated inflammation and tissue necrosis, the lesions are repaired and necrotic tissue is eliminated. The newly formed epithelium has numerous vessels, and connective tissue proliferation results in fibrosis of varying extent.

In both the above conditions, after repeated inflammation and tissue necrosis, the lesions are repaired and necrotic tissue is eliminated. The newly formed epithelium has numerous vessels, and connective tissue proliferation results in fibrosis of varying extent.

Colposcopic appearances

Before the application of acetic acid

Examination, before application of acetic acid, reveals moderate to excessive cervical and vaginal secretions, which may sometimes indicate the nature of underlying infection. In T. vaginalis infection (trichomoniasis), which is very common in tropical areas, there is copious, bubbly, frothy, malodorous, greenish-yellow, mucopurulent discharge. Bacterial infections are associated with thin, liquid, seropurulent discharge. The secretion may be foul-smelling in the case of anaerobic bacterial overgrowth, bacterial vaginosis, and Trichomonas infection. In the case of candidiasis (moniliasis) and other yeast infections, the secretion is thick and curdy (cheesy) white with intense itching resulting in a reddened vulva. Foul-smelling, dark-coloured mucopurulent discharges are associated with inflammatory states due to foreign bodies (e.g., a retained tampon). Gonorrhoea results in purulent vaginal discharge and cervical tenderness. Small vesicles filled with serous fluid may be observed in the cervix and vagina in the vesicular phase of herpes simplex viral infection. Herpetic infections are associated with episodes of painful vulvar, vaginal and cervical ulceration lasting for two weeks. Excoriation marks are evident with trichomoniasis, moniliasis and mixed bacterial infections.

A large coalesced ulcer due to herpes, or other inflammatory conditions, may mimic the appearance of invasive cancer. Chronic inflammation may cause recurrent ulceration and healing of the cervix, resulting in distortion of the cervix due to healing by fibrosis. There may be associated necrotic areas as well. A biopsy should be directed if in doubt. Rare and uncommon cervical infections, due to tuberculosis, schistosomiasis and amoebiasis, cause extensive ulceration and necrosis of the cervix with symptoms and signs mimicking invasive cancer; a biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

If the infectious process is accompanied by marked ulceration (with or without necrosis), the ulcerated area may be covered with purulent exudate, with marked differences in the surface level of the cervix. There may be exudation of serous droplets.

Longstanding bacterial, fungal or protozoal infection and inflammation may lead to fibrosis, which appears white or pink, depending on the degree of fibrosis. The epithelium covering the connective tissue is fragile, leading to ulceration and bleeding. Appearances following acetic acid and iodine application are variable, depending on the integrity of the surface epithelium.

In the case of cervicitis, the columnar epithelium is intensely red, bleeds on contact and opaque purulent discharge is present. The columnar villous or grape-like appearance may be lost due to flattening of the villi, to repeated inflammation and to the fact that there are no clearly defined papillae (Figure 9.1). Extensive areas of the cervix and infected vaginal mucosa appear red due to congestion of the underlying connective tissue.

A large coalesced ulcer due to herpes, or other inflammatory conditions, may mimic the appearance of invasive cancer. Chronic inflammation may cause recurrent ulceration and healing of the cervix, resulting in distortion of the cervix due to healing by fibrosis. There may be associated necrotic areas as well. A biopsy should be directed if in doubt. Rare and uncommon cervical infections, due to tuberculosis, schistosomiasis and amoebiasis, cause extensive ulceration and necrosis of the cervix with symptoms and signs mimicking invasive cancer; a biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

If the infectious process is accompanied by marked ulceration (with or without necrosis), the ulcerated area may be covered with purulent exudate, with marked differences in the surface level of the cervix. There may be exudation of serous droplets.

Longstanding bacterial, fungal or protozoal infection and inflammation may lead to fibrosis, which appears white or pink, depending on the degree of fibrosis. The epithelium covering the connective tissue is fragile, leading to ulceration and bleeding. Appearances following acetic acid and iodine application are variable, depending on the integrity of the surface epithelium.

In the case of cervicitis, the columnar epithelium is intensely red, bleeds on contact and opaque purulent discharge is present. The columnar villous or grape-like appearance may be lost due to flattening of the villi, to repeated inflammation and to the fact that there are no clearly defined papillae (Figure 9.1). Extensive areas of the cervix and infected vaginal mucosa appear red due to congestion of the underlying connective tissue.

figure 9.1: Reddish “angry-looking...

figure 9.1: Reddish “angry-looking...After application of acetic acid

The liberal application of acetic acid clears the cervix and vagina of secretions, but may cause pain. Cervicovaginitis is associated with oedema, capillary dilatation, enlargement of the stromal papillae, which contain the vascular bundles, and infiltration of the stroma with inflammatory cells. Chronically inflamed cervix may appear reddish, with ill-defined, patchy acetowhite areas scattered in the cervix, not restricted to the transformation zone and may bleed on touch (Figures 9.2, Figures 9.3). The enlarged stromal papillae appear as red spots (red punctation) in a pinkish-white background, usually in the case of T. vaginalis infection, after application of acetic acid. An inexperienced colposcopist may confuse the inflammatory punctations with those seen in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). However, one can differentiate using the following criteria: inflammatory punctations are fine, with extremely minimal intercapillary distances, and diffusely distributed (not restricted to the transformation zone) and they involve the original squamous epithelium and vagina with intervening inflamed mucosa. As the inflammation persists and becomes chronic, it results in large, focal red punctations due to large collections of capillaries grouped together, which appear as several red spots of different sizes visible in a pinkish- white background, producing the so-called ‘strawberry spots’ (Figure 9.4). Colposcopically, a chronically inflamed cervix may sometimes resemble invasive cervical cancer (Figure 9.5).

figure 9.2: Chronic cervicitis: th...

figure 9.2: Chronic cervicitis: th... figure 9.3: Chronic cervicitis: th...

figure 9.3: Chronic cervicitis: th... figure 9.4: Multiple red spots (a)...

figure 9.4: Multiple red spots (a)... figure 9.5: Colposcopic appearance...

figure 9.5: Colposcopic appearance...After application of Lugol’s iodine

The test outcome after application of Lugol’s iodine solution depends upon the desquamation and the loss of cell layers containing glycogen. If desquamation is limited to the summit of the stromal papillae where the squamous epithelium is thinnest, a series of thin yellow spots are seen on a mahogany-brown background, giving a stippled appearance (Figure 9.6). When the inflammation persists and the infection becomes chronic, the small desquamated areas become confluent to form large desquamated areas leading to the so-called leopard- skin appearance (Figure 9.7). These features are often found with Trichomonas infection, but also may be seen with fungal and bacterial infections. If there is marked desquamation, the cervix appears yellowish-red in colour, with involvement of vagina (Figure 9.8).

In summary, inflammatory conditions of the cervix are associated with excessive, usually malodorous, mucopurulent, seropurulent or whitish discharge, red punctations, ulceration, and healing by fibrosis. The secretion is frothy with bubbles in the case of trichomoniasis and sticky cheese white in candidiasis. Inflammatory lesions of the cervix may be differentiated from CIN by their large, diffuse involvement of the cervix, extension to the vagina, red colour tone and associated symptoms such as discharge and pruritus.

In summary, inflammatory conditions of the cervix are associated with excessive, usually malodorous, mucopurulent, seropurulent or whitish discharge, red punctations, ulceration, and healing by fibrosis. The secretion is frothy with bubbles in the case of trichomoniasis and sticky cheese white in candidiasis. Inflammatory lesions of the cervix may be differentiated from CIN by their large, diffuse involvement of the cervix, extension to the vagina, red colour tone and associated symptoms such as discharge and pruritus.

figure 9.6: Stippled appearance (a...

figure 9.6: Stippled appearance (a... figure 9.7: Trichomonas vaginalis ...

figure 9.7: Trichomonas vaginalis ... figure 9.8: Chronic cervicitis: th...

figure 9.8: Chronic cervicitis: th...