Home / Training / Manuals / Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginnersí manual / Chapter 8: Colposcopic diagnosis of preclinical invasive carcinoma of the cervix and glandular neoplasia

figure 8.1:

figure 8.1:

(a) There is a de... figure 8.2: Early invasive cancer:...

figure 8.2: Early invasive cancer:... figure 8.3:

Early invasive cancer...

figure 8.3:

Early invasive cancer... figure 8.4: Early invasive cancer:...

figure 8.4: Early invasive cancer:... figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter...

figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter... figure 8.6: Dense, chalky white co...

figure 8.6: Dense, chalky white co... figure 8.7: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 8.7: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.4: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 3.4: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.5: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 3.5: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.6: Advanced invasive cerv...

figure 3.6: Advanced invasive cerv... figure 8.8: Invasive cancer: There...

figure 8.8: Invasive cancer: There...

figure 8.9: A dense acetowhite le...

figure 8.9: A dense acetowhite le... figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter...

figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter... figure 8.10: Adenocarcinoma in sit...

figure 8.10: Adenocarcinoma in sit... figure 8.11: Adenocarcinoma in sit...

figure 8.11: Adenocarcinoma in sit... figure 8.12: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.12: Adenocarcinoma: Note ... figure 8.13: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.13: Adenocarcinoma: Note ... figure 8.14: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.14: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginnersí manual, Edited by J.W. Sellors and R. Sankaranarayanan

Chapter 8: Colposcopic diagnosis of preclinical invasive carcinoma of the cervix and glandular neoplasia

Filter by language: English / FranÁais / EspaŮol / Portugues / 中文- Acetowhite lesions with atypical vessels; large, complex acetowhite lesions obliterating the os; lesions with irregular and exophytic contour; strikingly thick, chalky-white lesions with raised and rolled out margins; and lesions bleeding on touch should be thoroughly investigated to rule out the possibility of early preclinical invasive cancer.

- Appearance of atypical blood vessels may indicate the first sign of invasion; one of the earliest colposcopic signs of invasion is blood vessels breaking out from mosaic formations.

- The atypical vessel patterns are varied and may take the form of hairpins, corkscrews, waste thread, commas, tadpole and other bizarre, irregular branching patterns with irregular calibre.

- Most glandular lesions originate in the transformation zone and may be associated with concomitant CIN lesions.

- Stark acetowhiteness of individual or fused villi in discrete patches in contrast to the surrounding columnar epithelium or closely placed, multiple cuffed crypt openings in a dense acetowhite lesion may indicate glandular lesions.

- Greyish-white, dense lesions with papillary excrescences and waste thread like or character writing-like atypical vessels or lesions with strikingly atypical villous structures may be associated with glandular lesions.

Invasive carcinoma is the stage of disease that follows CIN 3 or high-grade glandular intraepithelial neoplasia. Invasion implies that the neoplastic epithelial cells have invaded the stroma underlying the epithelium by breaching the basement membrane. The term preclinical invasive cancer is applied to very early invasive cancers (e.g., stage 1) in women without symptoms and gross physical findings and clinical signs, that are diagnosed incidentally during colposcopy or by other early-detection approaches such as screening. The primary responsibility of a colposcopist is to ensure that if preclinical invasive carcinoma of the cervix is present in a woman, it will be diagnosed. Colposcopic signs of this condition are usually recognizable early on, unless the lesion is hidden at the bottom of a crypt. This chapter describes the colposcopic detection of invasive cervical carcinomas followed by a specific consideration of cervical glandular neoplasia.

It is crucial for the colposcopist to become familiar with the signs of preclinical cervical cancer and understand the need for strict adherence to the diagnostic protocols that ensure the safety of women who are referred into their care. The use of colposcopy and directed biopsy as a diagnostic approach replaces the use of cervical cold-knife conization as the main diagnostic approach to women with cervical abnormalities. This means that the onus for diagnostic accuracy no longer rests solely on the pathologist who evaluates the cone specimen, but also on the colposcopist who provides the histological material for the pathologistís examination. The use of ablative treatment such as cryotherapy, in which no histological specimen of the treated area is available, further highlights this responsibility for strict adherence to colposcopy protocol and familiarity with signs of invasive carcinoma.

It is crucial for the colposcopist to become familiar with the signs of preclinical cervical cancer and understand the need for strict adherence to the diagnostic protocols that ensure the safety of women who are referred into their care. The use of colposcopy and directed biopsy as a diagnostic approach replaces the use of cervical cold-knife conization as the main diagnostic approach to women with cervical abnormalities. This means that the onus for diagnostic accuracy no longer rests solely on the pathologist who evaluates the cone specimen, but also on the colposcopist who provides the histological material for the pathologistís examination. The use of ablative treatment such as cryotherapy, in which no histological specimen of the treated area is available, further highlights this responsibility for strict adherence to colposcopy protocol and familiarity with signs of invasive carcinoma.

Colposcopic approach

The colposcopist should be well aware that invasive cancers are more common in older women and in those referred with high-grade cytological abnormalities. Large high-grade lesions, involving more than three quadrants of the cervix, should be thoroughly investigated for the possibility of early invasive cancer, especially if associated with atypical vessels. Other warning signs include the presence of a wide abnormal transformation zone (greater than 40 mm2), complex acetowhite lesions involving both lips of the cervix, lesions obliterating the os, lesions with irregular and exophytic surface contour, strikingly thick chalky white lesions with raised and rolled out margins, strikingly excessive atypical vessels, bleeding on touch or the presence of symptoms such as vaginal bleeding.

An advantage of performing a digital examination of the vagina and cervix before inserting the vaginal speculum is the opportunity to feel for any hint of nodularity or hardness of tissue. After the speculum is inserted, the cervix should have normal saline applied and the surface should be inspected for any suspicious lesions. Then the transformation zone should be identified, as described in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7. Colposcopic examination proceeds in the normal fashion (Chapter 6 and Chapter 7) with successive applications of saline, acetic acid and Lugolís iodine solution and careful observation after each.

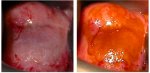

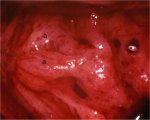

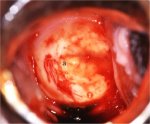

The colposcopic findings of preclinical invasive cervical cancer vary depending upon specific growth characteristics of the individual lesions, particularly early invasive lesions. The early preclinical invasive lesions turn densely greyish-white or yellowish-white very rapidly after the application of acetic acid (Figure 8.1). The acetowhiteness persists for several minutes.

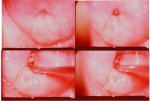

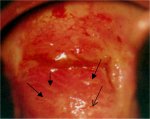

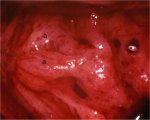

One of the earliest colposcopic signs of possible invasion is blood vessels breaking out from the mosaic formations and producing irregular longitudinal vessels (Figure 8.2). As the neoplastic process closely approaches the stage of invasive cancer, the blood vessels can take on increasingly irregular, bizarre patterns. Appearance of atypical vessels usually indicates the first signs of invasion (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.5). The key characteristics of these atypical surface vessels are that there is no gradual decrease in calibre (tapering) in the terminal branches and that the regular branching, seen in normal surface vessels, is absent. The atypical blood vessels, thought to be a result of horizontal pressure of the expanding neoplastic epithelium on the vascular spaces, show completely irregular and haphazard distribution, great variation in calibre with abrupt, angular changes in direction with bizarre branching and patterns. These vessel shapes have been described by labels such as wide hairpin, waste thread, bizarre waste thread, cork screw, tendril, root-like or tree-like vessels (Figure 8.5). They are irregular in size, shape, course and arrangement, and the intercapillary distance is substantially greater and more variable than that seen in normal epithelium.

If the cancer is predominantly exophytic, the lesion may appear as a raised growth with contact bleeding or capillary oozing. Early invasive carcinomas that are mainly exophytic tend to be soft and densely greyish-white in colour, with raised and rolled out margins (Figures 8.4 and 8.6). Surface bleeding or oozing is not uncommon, especially if there is a marked proliferation of atypical surface vessels (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.7). The bleeding may obliterate the acetowhiteness of the epithelium (Figures 8.2, 8.4 and 8.7). The atypical surface vessel types are varied and characteristically have widened intercapillary distances. These may take the form of hairpins, corkscrews, waste thread, commas, tadpole and other bizarre, irregular branching patterns and irregular calibre (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5 and 8.7). The abnormal branching vessels show a pattern of large vessels suddenly becoming smaller and then abruptly opening up again into a larger vessel. All of these abnormalities can best be detected with the green (or blue) filter and the use of a higher power of magnification. Proper evaluation of these abnormal vessel patterns, particularly with the green filter, constitutes a very important step in the colposcopic diagnosis of early invasive cervical cancers.

Early preclinical invasive cancer may also appear as dense, thick, chalky-white areas with surface irregularity and nodularity and with raised and rolled out margins (Figure 8.6). Such lesions may not present atypical blood vessel patterns and may not bleed on touch. Irregular surface contour with a mountains- and valleys- appearance is also characteristic of early invasive cancers (Figures 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.6 and 8.7). Colposcopically suspect early, preclinical invasive cancers are often very extensive, complex lesions involving all the quadrants of the cervix. Such lesions frequently involve the endocervical canal and may obliterate the external os. Infiltrating lesions appear as hard nodular white areas and may present necrotic areas in the centre. Invasive cancers of the cervix rarely produce glycogen and therefore, the lesions turn mustard yellow or saffron yellow after application of Lugolís iodine (Figures 8.1, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.7).

If a biopsy is taken of a lesion that is suspicious for invasive carcinoma and the report is negative for invasion, the responsibility rests with the colposcopist to ensure that a possibly more generous biopsy and an endocervical curettage (ECC) be taken at a subsequent examination. It is mandatory to take another biopsy if the pathologist reports that there is inadequate stromal tissue present on which to base a pathological decision as to whether invasion is present.

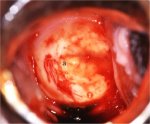

Advanced, frankly invasive cancers do not necessarily require colposcopy for diagnosis (Figures 3.4, Figures 3.5, 3.6 and 8.8). A properly conducted vaginal speculum examination with digital palpation should establish the diagnosis so that further confirmatory and staging investigations may be performed. Biopsy should be taken from the periphery of the growth, avoiding areas of necrosis, to ensure accurate histopathological diagnosis.

An advantage of performing a digital examination of the vagina and cervix before inserting the vaginal speculum is the opportunity to feel for any hint of nodularity or hardness of tissue. After the speculum is inserted, the cervix should have normal saline applied and the surface should be inspected for any suspicious lesions. Then the transformation zone should be identified, as described in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7. Colposcopic examination proceeds in the normal fashion (Chapter 6 and Chapter 7) with successive applications of saline, acetic acid and Lugolís iodine solution and careful observation after each.

The colposcopic findings of preclinical invasive cervical cancer vary depending upon specific growth characteristics of the individual lesions, particularly early invasive lesions. The early preclinical invasive lesions turn densely greyish-white or yellowish-white very rapidly after the application of acetic acid (Figure 8.1). The acetowhiteness persists for several minutes.

One of the earliest colposcopic signs of possible invasion is blood vessels breaking out from the mosaic formations and producing irregular longitudinal vessels (Figure 8.2). As the neoplastic process closely approaches the stage of invasive cancer, the blood vessels can take on increasingly irregular, bizarre patterns. Appearance of atypical vessels usually indicates the first signs of invasion (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.5). The key characteristics of these atypical surface vessels are that there is no gradual decrease in calibre (tapering) in the terminal branches and that the regular branching, seen in normal surface vessels, is absent. The atypical blood vessels, thought to be a result of horizontal pressure of the expanding neoplastic epithelium on the vascular spaces, show completely irregular and haphazard distribution, great variation in calibre with abrupt, angular changes in direction with bizarre branching and patterns. These vessel shapes have been described by labels such as wide hairpin, waste thread, bizarre waste thread, cork screw, tendril, root-like or tree-like vessels (Figure 8.5). They are irregular in size, shape, course and arrangement, and the intercapillary distance is substantially greater and more variable than that seen in normal epithelium.

If the cancer is predominantly exophytic, the lesion may appear as a raised growth with contact bleeding or capillary oozing. Early invasive carcinomas that are mainly exophytic tend to be soft and densely greyish-white in colour, with raised and rolled out margins (Figures 8.4 and 8.6). Surface bleeding or oozing is not uncommon, especially if there is a marked proliferation of atypical surface vessels (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.7). The bleeding may obliterate the acetowhiteness of the epithelium (Figures 8.2, 8.4 and 8.7). The atypical surface vessel types are varied and characteristically have widened intercapillary distances. These may take the form of hairpins, corkscrews, waste thread, commas, tadpole and other bizarre, irregular branching patterns and irregular calibre (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5 and 8.7). The abnormal branching vessels show a pattern of large vessels suddenly becoming smaller and then abruptly opening up again into a larger vessel. All of these abnormalities can best be detected with the green (or blue) filter and the use of a higher power of magnification. Proper evaluation of these abnormal vessel patterns, particularly with the green filter, constitutes a very important step in the colposcopic diagnosis of early invasive cervical cancers.

Early preclinical invasive cancer may also appear as dense, thick, chalky-white areas with surface irregularity and nodularity and with raised and rolled out margins (Figure 8.6). Such lesions may not present atypical blood vessel patterns and may not bleed on touch. Irregular surface contour with a mountains- and valleys- appearance is also characteristic of early invasive cancers (Figures 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.6 and 8.7). Colposcopically suspect early, preclinical invasive cancers are often very extensive, complex lesions involving all the quadrants of the cervix. Such lesions frequently involve the endocervical canal and may obliterate the external os. Infiltrating lesions appear as hard nodular white areas and may present necrotic areas in the centre. Invasive cancers of the cervix rarely produce glycogen and therefore, the lesions turn mustard yellow or saffron yellow after application of Lugolís iodine (Figures 8.1, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.7).

If a biopsy is taken of a lesion that is suspicious for invasive carcinoma and the report is negative for invasion, the responsibility rests with the colposcopist to ensure that a possibly more generous biopsy and an endocervical curettage (ECC) be taken at a subsequent examination. It is mandatory to take another biopsy if the pathologist reports that there is inadequate stromal tissue present on which to base a pathological decision as to whether invasion is present.

Advanced, frankly invasive cancers do not necessarily require colposcopy for diagnosis (Figures 3.4, Figures 3.5, 3.6 and 8.8). A properly conducted vaginal speculum examination with digital palpation should establish the diagnosis so that further confirmatory and staging investigations may be performed. Biopsy should be taken from the periphery of the growth, avoiding areas of necrosis, to ensure accurate histopathological diagnosis.

figure 8.1:

figure 8.1:(a) There is a de...

figure 8.2: Early invasive cancer:...

figure 8.2: Early invasive cancer:... figure 8.3:

Early invasive cancer...

figure 8.3:

Early invasive cancer... figure 8.4: Early invasive cancer:...

figure 8.4: Early invasive cancer:... figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter...

figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter... figure 8.6: Dense, chalky white co...

figure 8.6: Dense, chalky white co... figure 8.7: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 8.7: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.4: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 3.4: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.5: Invasive cervical canc...

figure 3.5: Invasive cervical canc... figure 3.6: Advanced invasive cerv...

figure 3.6: Advanced invasive cerv... figure 8.8: Invasive cancer: There...

figure 8.8: Invasive cancer: There...Glandular lesions

There are no obvious colposcopic features that allow definite diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in-situ (AIS) and adenocarcinoma, as no firm criteria have been established and widely accepted for recognizing glandular lesions. Most cervical AIS or early adenocarcinoma is discovered incidentally after biopsy for squamous intraepithelial neoplasia. It is worth noting that often AIS coexists with CIN. The colposcopic diagnosis of AIS and adenocarcinoma require a high degree of training and skill.

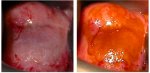

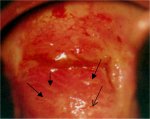

It has been suggested that most glandular lesions originate within the transformation zone and colposcopic recognition of the stark acetowhiteness of either the individual or fused villi in discrete patches (in contrast to the surrounding pinkish white columnar villi) may lead to a colposcopic suspicion of glandular lesions. While CIN lesions are almost always connected with the squamocolumnar junction, glandular lesions may present densely white island lesions in the columnar epithelium (Figure 8.9). In approximately half of women with AIS, the lesion is entirely within the canal (Figure 8.9) and may easily be missed if the endocervical canal is not properly visualized and investigated.

A lesion in the columnar epithelium containing branch-like or root-like vessels (Figure 8.5) may also suggest glandular disease. Strikingly acetowhite columnar villi in stark contrast to the surrounding villi may suggest glandular lesions (Figure 8.10). Elevated lesions with an irregular acetowhite surface, papillary patterns and atypical blood vessels overlying the columnar epithelium may be associated with glandular lesions (Figure 8.11). A variegated patchy red and white lesion with small papillary excrescences and epithelial buddings and large crypt openings in the columnar epithelium may also be associated with glandular lesions.

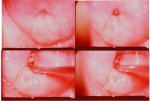

Invasive adenocarcinoma may present as greyish-white dense acetowhite lesions with papillary excrescences and waste thread-like or character writing-like atypical blood vessels (Figure 8.12). The soft surface may come off easily when touched with a cotton applicator. Adenocarcinoma may also present as strikingly atypical villous structures with atypical vessels replacing normal ectocervical columnar epithelium (Figure 8.13). Closely placed, multiple cuffed crypt openings in a dense acetowhite lesion with irregular surface may also indicate a glandular lesion (Figure 8.14).

In summary, the accurate colposcopic diagnosis of preclinical invasive carcinoma and glandular lesions depends on several factors: continuing alertness on the part of the colposcopist, strict adherence to the step-by-step approach to examination, the use of a grading index, close attention to surface blood vessels, the honest appraisal of when an examination is inadequate, the appropriate use of ECC to rule out lesions in the canal, and the taking of a well directed biopsy of sufficient tissue on which to base a reliable histopathological diagnosis.

It has been suggested that most glandular lesions originate within the transformation zone and colposcopic recognition of the stark acetowhiteness of either the individual or fused villi in discrete patches (in contrast to the surrounding pinkish white columnar villi) may lead to a colposcopic suspicion of glandular lesions. While CIN lesions are almost always connected with the squamocolumnar junction, glandular lesions may present densely white island lesions in the columnar epithelium (Figure 8.9). In approximately half of women with AIS, the lesion is entirely within the canal (Figure 8.9) and may easily be missed if the endocervical canal is not properly visualized and investigated.

A lesion in the columnar epithelium containing branch-like or root-like vessels (Figure 8.5) may also suggest glandular disease. Strikingly acetowhite columnar villi in stark contrast to the surrounding villi may suggest glandular lesions (Figure 8.10). Elevated lesions with an irregular acetowhite surface, papillary patterns and atypical blood vessels overlying the columnar epithelium may be associated with glandular lesions (Figure 8.11). A variegated patchy red and white lesion with small papillary excrescences and epithelial buddings and large crypt openings in the columnar epithelium may also be associated with glandular lesions.

Invasive adenocarcinoma may present as greyish-white dense acetowhite lesions with papillary excrescences and waste thread-like or character writing-like atypical blood vessels (Figure 8.12). The soft surface may come off easily when touched with a cotton applicator. Adenocarcinoma may also present as strikingly atypical villous structures with atypical vessels replacing normal ectocervical columnar epithelium (Figure 8.13). Closely placed, multiple cuffed crypt openings in a dense acetowhite lesion with irregular surface may also indicate a glandular lesion (Figure 8.14).

In summary, the accurate colposcopic diagnosis of preclinical invasive carcinoma and glandular lesions depends on several factors: continuing alertness on the part of the colposcopist, strict adherence to the step-by-step approach to examination, the use of a grading index, close attention to surface blood vessels, the honest appraisal of when an examination is inadequate, the appropriate use of ECC to rule out lesions in the canal, and the taking of a well directed biopsy of sufficient tissue on which to base a reliable histopathological diagnosis.

figure 8.9: A dense acetowhite le...

figure 8.9: A dense acetowhite le... figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter...

figure 8.5: Atypical vessel patter... figure 8.10: Adenocarcinoma in sit...

figure 8.10: Adenocarcinoma in sit... figure 8.11: Adenocarcinoma in sit...

figure 8.11: Adenocarcinoma in sit... figure 8.12: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.12: Adenocarcinoma: Note ... figure 8.13: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.13: Adenocarcinoma: Note ... figure 8.14: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...

figure 8.14: Adenocarcinoma: Note ...