Home / Training / Manuals / Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners’ manual / Chapter 2: An Introduction to Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN)

table 2.1: Correlation between dys...

table 2.1: Correlation between dys... table 2.2: The 2001 Bethesda Syste...

table 2.2: The 2001 Bethesda Syste...

figure 2.1: Cytological appearance...

figure 2.1: Cytological appearance...

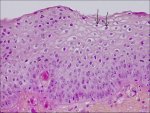

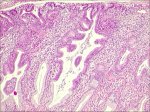

figure2.2: Histology of CIN 1: Not...

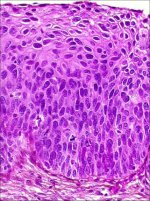

figure2.2: Histology of CIN 1: Not... figure 2.3: Histology of CIN 2: At...

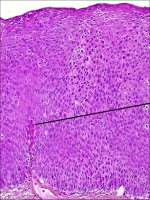

figure 2.3: Histology of CIN 2: At... figure 2.4: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...

figure 2.4: Histology of CIN 3: Dy... figure 2.5: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...

figure 2.5: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...

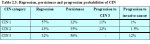

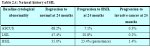

table 2.3: Regression, persistence...

table 2.3: Regression, persistence... table 2.4: Natural history of SIL<...

table 2.4: Natural history of SIL<...

figure 2.6: Adenocarcinoma in situ...

figure 2.6: Adenocarcinoma in situ...

Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners’ manual, Edited by J.W. Sellors and R. Sankaranarayanan

Chapter 2: An Introduction to Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN)

Filter by language: English / Français / Español / Portugues / 中文- Invasive squamous cell cervical cancers are preceded by a long phase of preinvasive disease, collectively referred to as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

- CIN may be categorized into grades 1, 2 and 3 depending upon the proportion of the thickness of the epithelium showing mature and differentiated cells.

- More severe grades of CIN (2 and 3) reveal a greater proportion of the thickness of the epithelium composed of undifferentiated cells.

- Persistent infection with one or more of the oncogenic subtypes of human papillomaviruses (HPV) is a necessary cause for cervical neoplasia.

- Most cervical abnormalities caused by HPV infection are unlikely to progress to high-grade CIN or cervical cancer.

- Most low-grade CIN regress within relatively short periods or do not progress to high-grade lesions.

- High-grade CIN carries a much higher probability of progressing to invasive cancer.

- The precursor lesion arising from the columnar epithelium is referred to as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). AIS may be associated with CIN in one-to two-thirds of cases.

Invasive cervical cancers are usually preceded by a long phase of preinvasive disease. This is characterized microscopically as a spectrum of events progressing from cellular atypia to various grades of dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) before progression to invasive carcinoma. A good knowledge of the etiology, pathophysiology and natural history of CIN provides a strong basis both for visual testing and for colposcopic diagnosis and understanding the principles of treatment of these lesions. This chapter describes the evolution of the classification systems of cervical squamous cell cancer precursors, the cytological and histological basis of their diagnosis, as well as their natural history in terms of regression, persistence and progression rates. It also describes the precancerous lesions arising in the cervical columnar epithelium, commonly referred to as glandular lesions.

The concept of cervical cancer precursors dates back to the late nineteenth century, when areas of non-invasive atypical epithelial changes were recognized in tissue specimens adjacent to invasive cancers ( William, 1888). The term carcinoma in situ (CIS) was introduced in 1932 to denote those lesions in which the undifferentiated carcinomatous cells involved the full thickness of the epithelium, without disruption of the basement membrane ( Broders, 1932). The association between CIS and invasive cervical cancer was subsequently reported. The term dysplasia was introduced in the late 1950s to designate the cervical epithelial atypia that is intermediate between the normal epithelium and CIS ( Reagan et al., 19.3). Dysplasia was further categorized into three groups – mild, moderate and severe – depending on the degree of involvement of the epithelial thickness by the atypical cells. Subsequently, for many years, cervical precancerous lesions were reported using the categories of dysplasia and CIS, and are still widely used in many developing countries.

A system of classification with separate classes for dysplasia and CIS was increasingly perceived as an arbitrary configuration, based upon the findings from a number of follow-up studies involving women with such lesions. It was observed that some cases of dysplasia regressed, some persisted and others progressed to CIS. A direct correlation with progression and histological grade was observed. These observations led to the concept of a single, continuous disease process by which normal epithelium evolves into epithelial precursor lesions and on to invasive cancer. On the basis of the above observations, the term cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was introduced in 1968 to denote the whole range of cellular atypia confined to the epithelium. CIN was divided into grades 1, 2 and 3 ( Richart 1968). CIN 1 corresponded to mild dysplasia, CIN 2 to moderate dysplasia, and CIN 3 corresponded to both severe dysplasia and CIS.

In the 1980s, the pathological changes such as koilocytic or condylomatous atypia associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection were increasingly recognized. Koilocytes are atypical cells with a perinuclear cavitation or halo in the cytoplasm indicating the cytopathic changes due to HPV infection. This led to the development of a simplified two-grade histological system. Thus, in 1990, a histopathological terminology based on two grades of disease was proposed: low-grade CIN comprising the abnormalities consistent with koilocytic atypia and CIN 1 lesions and high-grade CIN comprising CIN 2 and 3. The high-grade lesions were considered to be true precursors of invasive cancer ( Richart 1990).

In 1988, the US National Cancer Institute convened a workshop to propose a new scheme for reporting cervical cytology results ( NCI workshop report, 1989; Solomon, 1989; Kurman et al., 1991). The recommendations from this workshop and the subsequent revision in a second workshop held in 1991 became known as the Bethesda system (TBS) ( NCI workshop report, 1992). The main feature of TBS was the creation of the term squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), and a two-grade scheme consisting of low-grade (LSIL) and high-grade (HSIL) lesions. TBS classification combines flat condylomatous (HPV) changes and low-grade CIN (CIN 1) into LSIL, while the HSIL encompasses more advanced CIN such as CIN 2 and 3. The term lesion was used to emphasize that any of the morphological changes upon which a diagnosis is based do not necessarily identify a neoplastic process. Though designed for cytological reporting, TBS is also used to report histopathology findings. TBS is predominantly used in North America. The correlation between the dysplasia/carcinoma in situ terminology and the various grades of CIN, as well as TBS, are given in Table 2.1. We use the CIN terminology in discussing the various grades of cervical squamous precancerous lesions in this manual.

TBS was reevaluated and revised in a 2001 workshop convened by the National Cancer Institute, USA, cosponsored by 44 professional societies representing more than 20 countries ( Solomon et al., 2002). The reporting categories under the 2001 Bethesda System are summarized in Table 2.2.

The concept of cervical cancer precursors dates back to the late nineteenth century, when areas of non-invasive atypical epithelial changes were recognized in tissue specimens adjacent to invasive cancers ( William, 1888). The term carcinoma in situ (CIS) was introduced in 1932 to denote those lesions in which the undifferentiated carcinomatous cells involved the full thickness of the epithelium, without disruption of the basement membrane ( Broders, 1932). The association between CIS and invasive cervical cancer was subsequently reported. The term dysplasia was introduced in the late 1950s to designate the cervical epithelial atypia that is intermediate between the normal epithelium and CIS ( Reagan et al., 19.3). Dysplasia was further categorized into three groups – mild, moderate and severe – depending on the degree of involvement of the epithelial thickness by the atypical cells. Subsequently, for many years, cervical precancerous lesions were reported using the categories of dysplasia and CIS, and are still widely used in many developing countries.

A system of classification with separate classes for dysplasia and CIS was increasingly perceived as an arbitrary configuration, based upon the findings from a number of follow-up studies involving women with such lesions. It was observed that some cases of dysplasia regressed, some persisted and others progressed to CIS. A direct correlation with progression and histological grade was observed. These observations led to the concept of a single, continuous disease process by which normal epithelium evolves into epithelial precursor lesions and on to invasive cancer. On the basis of the above observations, the term cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was introduced in 1968 to denote the whole range of cellular atypia confined to the epithelium. CIN was divided into grades 1, 2 and 3 ( Richart 1968). CIN 1 corresponded to mild dysplasia, CIN 2 to moderate dysplasia, and CIN 3 corresponded to both severe dysplasia and CIS.

In the 1980s, the pathological changes such as koilocytic or condylomatous atypia associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection were increasingly recognized. Koilocytes are atypical cells with a perinuclear cavitation or halo in the cytoplasm indicating the cytopathic changes due to HPV infection. This led to the development of a simplified two-grade histological system. Thus, in 1990, a histopathological terminology based on two grades of disease was proposed: low-grade CIN comprising the abnormalities consistent with koilocytic atypia and CIN 1 lesions and high-grade CIN comprising CIN 2 and 3. The high-grade lesions were considered to be true precursors of invasive cancer ( Richart 1990).

In 1988, the US National Cancer Institute convened a workshop to propose a new scheme for reporting cervical cytology results ( NCI workshop report, 1989; Solomon, 1989; Kurman et al., 1991). The recommendations from this workshop and the subsequent revision in a second workshop held in 1991 became known as the Bethesda system (TBS) ( NCI workshop report, 1992). The main feature of TBS was the creation of the term squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), and a two-grade scheme consisting of low-grade (LSIL) and high-grade (HSIL) lesions. TBS classification combines flat condylomatous (HPV) changes and low-grade CIN (CIN 1) into LSIL, while the HSIL encompasses more advanced CIN such as CIN 2 and 3. The term lesion was used to emphasize that any of the morphological changes upon which a diagnosis is based do not necessarily identify a neoplastic process. Though designed for cytological reporting, TBS is also used to report histopathology findings. TBS is predominantly used in North America. The correlation between the dysplasia/carcinoma in situ terminology and the various grades of CIN, as well as TBS, are given in Table 2.1. We use the CIN terminology in discussing the various grades of cervical squamous precancerous lesions in this manual.

TBS was reevaluated and revised in a 2001 workshop convened by the National Cancer Institute, USA, cosponsored by 44 professional societies representing more than 20 countries ( Solomon et al., 2002). The reporting categories under the 2001 Bethesda System are summarized in Table 2.2.

table 2.1: Correlation between dys...

table 2.1: Correlation between dys... table 2.2: The 2001 Bethesda Syste...

table 2.2: The 2001 Bethesda Syste...Clinical features of CIN

There are no specific symptoms and no characteristic clinical features that indicate the presence of CIN. Many of these lesions, however, may turn white on application of 3-5% acetic acid, and may be iodine-negative on application of Lugol’s iodine solution, as the CIN epithelium contains little or no glycogen.

Diagnosis and grading of CIN by cytology

CIN may be identified by microscopic examination of cervical cells in a cytology smear stained by the Papanicolaou technique. In cytological preparations, individual cell changes are assessed for the diagnosis of CIN and its grading. In contrast, histological examination of whole tissues allows several other features to be examined. Cytological assessment of CIN, based on nuclear and cytoplasmic changes is often quite challenging (Figure 2.1).

Nuclear enlargement with variation in size and shape is a regular feature of all dysplastic cells (Figure 2.1). Increased intensity of staining (hyperchromasia) is another prominent feature. Irregular chromatin distribution with clumping is always present in dysplastic cells. Mitotic figures and visible nucleoli are uncommon in cytological smears. Abnormal nuclei in superficial or intermediate cells indicate a low-grade CIN, whereas abnormality in nuclei of parabasal and basal cells indicates high-grade CIN. The amount of cytoplasm in relation to the size of the nucleus (nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio) is one of the most important base for assessing the grade of CIN (Figure 2.1). Increased ratios are associated with more severe degrees of CIN. More often than not, a cervical smear contains cells with a range of changes; considerable challenges and subjectivity, therefore, are involved in reporting the results. Experience of the cytologist is critically important in final reporting.

Nuclear enlargement with variation in size and shape is a regular feature of all dysplastic cells (Figure 2.1). Increased intensity of staining (hyperchromasia) is another prominent feature. Irregular chromatin distribution with clumping is always present in dysplastic cells. Mitotic figures and visible nucleoli are uncommon in cytological smears. Abnormal nuclei in superficial or intermediate cells indicate a low-grade CIN, whereas abnormality in nuclei of parabasal and basal cells indicates high-grade CIN. The amount of cytoplasm in relation to the size of the nucleus (nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio) is one of the most important base for assessing the grade of CIN (Figure 2.1). Increased ratios are associated with more severe degrees of CIN. More often than not, a cervical smear contains cells with a range of changes; considerable challenges and subjectivity, therefore, are involved in reporting the results. Experience of the cytologist is critically important in final reporting.

figure 2.1: Cytological appearance...

figure 2.1: Cytological appearance...Diagnosis and grading of CIN by histopathology

CIN may be suspected through cytological examination using the Papanicolaou technique or through colposcopic examination. Final diagnosis of CIN is established by the histopathological examination of a cervical punch biopsy or excision specimen. A judgement of whether or not a cervical tissue specimen reveals CIN, and to what degree, is dependent on the histological features concerned with differentiation, maturation and stratification of cells and nuclear abnormalities. The proportion of the thickness of the epithelium showing mature and differentiated cells is used for grading CIN. More severe degrees of CIN are likely to have a greater proportion of the thickness of epithelium composed of undifferentiated cells, with only a narrow layer of mature, differentiated cells on the surface.

Nuclear abnormalities such as enlarged nuclei, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, increased intensity of nuclear staining (hyperchromasia), nuclear polymorphism and variation in nuclear size (anisokaryosis) are assessed when a diagnosis is being made. There is often a strong correlation between the proportion of epithelium revealing maturation and the degree of nuclear abnormality. Mitotic figures are seen in cells that are in cell division; they are infrequent in normal epithelium and, if present, they are seen only in the parabasal layer. As the severity of CIN increases, the number of mitotic figures also increases; these may be seen in the superficial layers of the epithelium. The less differentiation in an epithelium, the higher the level at which mitotic figures are likely to be seen. Abnormal configurations of mitotic figures also are taken into account in arriving at final diagnosis.

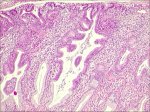

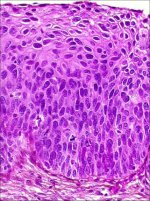

In CIN 1 there is good maturation with minimal nuclear abnormalities and few mitotic figures (Figure 2.2). Undifferentiated cells are confined to the deeper layers (lower third) of the epithelium. Mitotic figures are present, but not very numerous. Cytopathic changes due to HPV infection may be observed in the full thickness of the epithelium.

CIN 2 is characterized by dysplastic cellular changes mostly restricted to the lower half or the lower two-thirds of the epithelium, with more marked nuclear abnormalities than in CIN 1 (Figure 2.3). Mitotic figures may be seen throughout the lower half of the epithelium.

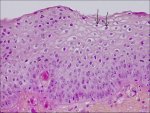

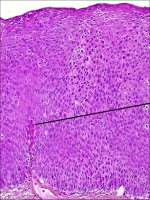

In CIN 3, differentiation and stratification may be totally absent or present only in the superficial quarter of the epithelium with numerous mitotic figures (Figures 2.4 and Figures 2.5). Nuclear abnormalities extend throughout the thickness of the epithelium. Many mitotic figures have abnormal forms.

A close interaction between cytologists, histopathologists and colposcopists improves reporting in all three disciplines. This particularly helps in differentiating milder degrees of CIN from other conditions with which there can be confusion.

Nuclear abnormalities such as enlarged nuclei, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, increased intensity of nuclear staining (hyperchromasia), nuclear polymorphism and variation in nuclear size (anisokaryosis) are assessed when a diagnosis is being made. There is often a strong correlation between the proportion of epithelium revealing maturation and the degree of nuclear abnormality. Mitotic figures are seen in cells that are in cell division; they are infrequent in normal epithelium and, if present, they are seen only in the parabasal layer. As the severity of CIN increases, the number of mitotic figures also increases; these may be seen in the superficial layers of the epithelium. The less differentiation in an epithelium, the higher the level at which mitotic figures are likely to be seen. Abnormal configurations of mitotic figures also are taken into account in arriving at final diagnosis.

In CIN 1 there is good maturation with minimal nuclear abnormalities and few mitotic figures (Figure 2.2). Undifferentiated cells are confined to the deeper layers (lower third) of the epithelium. Mitotic figures are present, but not very numerous. Cytopathic changes due to HPV infection may be observed in the full thickness of the epithelium.

CIN 2 is characterized by dysplastic cellular changes mostly restricted to the lower half or the lower two-thirds of the epithelium, with more marked nuclear abnormalities than in CIN 1 (Figure 2.3). Mitotic figures may be seen throughout the lower half of the epithelium.

In CIN 3, differentiation and stratification may be totally absent or present only in the superficial quarter of the epithelium with numerous mitotic figures (Figures 2.4 and Figures 2.5). Nuclear abnormalities extend throughout the thickness of the epithelium. Many mitotic figures have abnormal forms.

A close interaction between cytologists, histopathologists and colposcopists improves reporting in all three disciplines. This particularly helps in differentiating milder degrees of CIN from other conditions with which there can be confusion.

figure2.2: Histology of CIN 1: Not...

figure2.2: Histology of CIN 1: Not... figure 2.3: Histology of CIN 2: At...

figure 2.3: Histology of CIN 2: At... figure 2.4: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...

figure 2.4: Histology of CIN 3: Dy... figure 2.5: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...

figure 2.5: Histology of CIN 3: Dy...Etiopathogenesis of cervical neoplasia

Epidemiological studies have identified a number of risk factors that contribute to the development of cervical cancer precursors and cervical cancer. These include infection with certain oncogenic types of human papillomaviruses (HPV), sexual intercourse at an early age, multiple sexual partners, multiparity, long-term oral contraceptive use, tobacco smoking, low socioeconomic status, infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, micronutrient deficiency and a diet deficient in vegetables and fruits ( IARC, 19.5; Bosch et al., 19.5; Schiffman et al., 1996; Walboomers et al., 1999; Franco et al., 1999; Ferenczy & Franco, 2002).

HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68 are strongly associated with CIN and invasive cancer ( IARC, 19.5; Walboomers et al., 1999). Persistent infection with one or more of the above oncogenic types is considered to be a necessary cause for cervical neoplasia ( IARC, 19.5). The pooled analysis of results from a multicentre case-control study conducted by the International Agency for Research on Cancer ( IARC, 19.5) revealed relative risks (RR) ranging from 17 in Colombia to 156 in the Philippines, with a pooled RR of 60 (95% confidence interval: 49-73) for cervical cancer ( Walboomers et al., 1999). The association was equally strong for squamous cell carcinoma (RR: 62) and adenocarcinoma of the cervix (RR: 51). HPV DNA was detected in 99.7% of 1000 evaluable cervical cancer biopsy specimens obtained from 22 countries ( Walboomers et al., 1999; Franco et al., 1999). HPV 16 and 18 are the main viral genotypes found in cervical cancers worldwide.

Several cohort (follow-up) studies have reported a strong association between persistent oncogenic HPV infection and high risk of developing CIN ( Koutsky et al., 1992; Ho et al., 19.5; Ho et al., 1998; Moscicki et al., 1998; Liaw et al., 1999; Wallin et al., 1999; Moscicki et al., 2001; Woodman et al., 2001; Schlecht et al., 2002).

HPV infection is transmitted through sexual contact and the risk factors therefore are closely related to sexual behaviour (e.g., lifetime number of sexual partners, sexual intercourse at an early age). In most women, HPV infections are transient. The natural history of HPV infection has been extensively reviewed. Although the prevalence of HPV infection varies in different regions of the world, it generally reaches a peak of about 20-30% among women aged 20-24 years, with a subsequent decline to approximately 3-10% among women aged over 30 ( Herrero et al., 1997a; Herrero et al., 1997b; Sellors et al., 2000). About 80% of young women who become infected with HPV have transient infections that clear up within 12-18 months ( Ho et al., 1998; Franco et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2000; Liaw et al., 2001).

HPV infection is believed to start in the basal cells or parabasal cells of the metaplastic epithelium. If the infection persists, integration of viral genome into the host cellular genome may occur. The normal differentiation and maturation of the immature squamous metaplastic into the mature squamous metaplastic epithelium may be disrupted as a result of expression of E6/E7 oncoproteins and the loss of normal growth control. This may then lead to development of abnormal dysplastic epithelium. If the neoplastic process continues uninterrupted, the early low-grade lesions may eventually involve the full thickness of the epithelium. Subsequently the disease may traverse the basement membrane and become invasive cancer, extending to surrounding tissues and organs. The invasion may then affect blood and lymphatic vessels and the disease may spread to the lymph nodes and distant organs.

HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68 are strongly associated with CIN and invasive cancer ( IARC, 19.5; Walboomers et al., 1999). Persistent infection with one or more of the above oncogenic types is considered to be a necessary cause for cervical neoplasia ( IARC, 19.5). The pooled analysis of results from a multicentre case-control study conducted by the International Agency for Research on Cancer ( IARC, 19.5) revealed relative risks (RR) ranging from 17 in Colombia to 156 in the Philippines, with a pooled RR of 60 (95% confidence interval: 49-73) for cervical cancer ( Walboomers et al., 1999). The association was equally strong for squamous cell carcinoma (RR: 62) and adenocarcinoma of the cervix (RR: 51). HPV DNA was detected in 99.7% of 1000 evaluable cervical cancer biopsy specimens obtained from 22 countries ( Walboomers et al., 1999; Franco et al., 1999). HPV 16 and 18 are the main viral genotypes found in cervical cancers worldwide.

Several cohort (follow-up) studies have reported a strong association between persistent oncogenic HPV infection and high risk of developing CIN ( Koutsky et al., 1992; Ho et al., 19.5; Ho et al., 1998; Moscicki et al., 1998; Liaw et al., 1999; Wallin et al., 1999; Moscicki et al., 2001; Woodman et al., 2001; Schlecht et al., 2002).

HPV infection is transmitted through sexual contact and the risk factors therefore are closely related to sexual behaviour (e.g., lifetime number of sexual partners, sexual intercourse at an early age). In most women, HPV infections are transient. The natural history of HPV infection has been extensively reviewed. Although the prevalence of HPV infection varies in different regions of the world, it generally reaches a peak of about 20-30% among women aged 20-24 years, with a subsequent decline to approximately 3-10% among women aged over 30 ( Herrero et al., 1997a; Herrero et al., 1997b; Sellors et al., 2000). About 80% of young women who become infected with HPV have transient infections that clear up within 12-18 months ( Ho et al., 1998; Franco et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2000; Liaw et al., 2001).

HPV infection is believed to start in the basal cells or parabasal cells of the metaplastic epithelium. If the infection persists, integration of viral genome into the host cellular genome may occur. The normal differentiation and maturation of the immature squamous metaplastic into the mature squamous metaplastic epithelium may be disrupted as a result of expression of E6/E7 oncoproteins and the loss of normal growth control. This may then lead to development of abnormal dysplastic epithelium. If the neoplastic process continues uninterrupted, the early low-grade lesions may eventually involve the full thickness of the epithelium. Subsequently the disease may traverse the basement membrane and become invasive cancer, extending to surrounding tissues and organs. The invasion may then affect blood and lymphatic vessels and the disease may spread to the lymph nodes and distant organs.

Natural history of cervical cancer precursors

Despite women’s frequent exposure to HPV, development of cervical neoplasia is uncommon. Most cervical abnormalities caused by HPV infection are unlikely to progress to high-grade CIN or cervical cancer, as most of them regress by themselves. The long time frame between initial infection and overt disease indicates that several cofactors (e.g., genetic differences, hormonal effects, micronutrient deficiencies, smoking, or chronic inflammation) may be necessary for disease progression. Spontaneous regression of CIN may also indicate that many women may not be exposed to these cofactors.

Several studies have addressed the natural history of CIN, with particular emphasis on disease regression, persistence and progression ( McIndoe et al., 1984; Ostor et al., 19.3; Mitchell et al., 1994; Melinkow et al., 1998; Holowaty et al., (1999)). They have revealed that most low-grade lesions are transient; most of them regress to normal within relatively short periods or do not progress to more severe forms. High-grade CIN, on the other hand, carries a much higher probability of progressing to invasive cancer, although a proportion of such lesions also regress or persist. It is appears that the mean interval for progression of cervical precursors to invasive cancer is some 10 to 20 years.

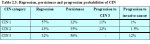

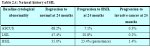

A few studies have attempted to summarize the rates of regression, persistence and progression of CIN. Even though these studies have many limitations, they provide interesting insight into the biological behaviour of these lesions. The results of a pooled analysis of studies published from 1950 to 1993 are given in Table 2.3 ( Ostor et al., 19.3). In another overview, the cumulative probabilities for all grades of CIN that had been followed by both cytology and histology were 45% for regression, 31% for persistence, and 23% for progression ( Mitchell et al., 1994). Progression rates to invasive cancer for studies following up CIS patients by biopsy ranged from 29 to 36% ( McIndoe et al., 1984). A meta analysis of 27000 women gave the weighted average rates of progression to HSIL and invasive cancer at 24 months according to baseline cytological abnormality given in Table 2.4 ( Melinkow et al., 1998). Holowaty et al., (1999) calculated RR of progression and regression by 2-years of follow-up for moderate and severe dysplasias, with mild dysplasia taken as the baseline reference category. RRs for CIS were 8.1 for moderate dysplasia and 22.7 for severe dysplasia. The corresponding RRs for invasive cancer were 4.5 and 20.7, respectively.

Several studies have addressed the natural history of CIN, with particular emphasis on disease regression, persistence and progression ( McIndoe et al., 1984; Ostor et al., 19.3; Mitchell et al., 1994; Melinkow et al., 1998; Holowaty et al., (1999)). They have revealed that most low-grade lesions are transient; most of them regress to normal within relatively short periods or do not progress to more severe forms. High-grade CIN, on the other hand, carries a much higher probability of progressing to invasive cancer, although a proportion of such lesions also regress or persist. It is appears that the mean interval for progression of cervical precursors to invasive cancer is some 10 to 20 years.

A few studies have attempted to summarize the rates of regression, persistence and progression of CIN. Even though these studies have many limitations, they provide interesting insight into the biological behaviour of these lesions. The results of a pooled analysis of studies published from 1950 to 1993 are given in Table 2.3 ( Ostor et al., 19.3). In another overview, the cumulative probabilities for all grades of CIN that had been followed by both cytology and histology were 45% for regression, 31% for persistence, and 23% for progression ( Mitchell et al., 1994). Progression rates to invasive cancer for studies following up CIS patients by biopsy ranged from 29 to 36% ( McIndoe et al., 1984). A meta analysis of 27000 women gave the weighted average rates of progression to HSIL and invasive cancer at 24 months according to baseline cytological abnormality given in Table 2.4 ( Melinkow et al., 1998). Holowaty et al., (1999) calculated RR of progression and regression by 2-years of follow-up for moderate and severe dysplasias, with mild dysplasia taken as the baseline reference category. RRs for CIS were 8.1 for moderate dysplasia and 22.7 for severe dysplasia. The corresponding RRs for invasive cancer were 4.5 and 20.7, respectively.

table 2.3: Regression, persistence...

table 2.3: Regression, persistence... table 2.4: Natural history of SIL<...

table 2.4: Natural history of SIL<...Adenocarcinoma in situ

The precursor lesion that has been recognized to arise from the columnar epithelium is referred to as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). In AIS, normal columnar epithelium is replaced by abnormal epithelium showing loss of polarity, increased cell size, increased nuclear size, nuclear hyperchromasia, mitotic activity, reduction of cytoplasmic mucin expression and cellular stratification or piling (Figure 2.6). Abnormal branching and budding glands with intraluminal papillary epithelial projections lacking stromal cores may also be observed. It may be sub-divided based on the cell types into endocervical, endometroid, intestinal and mixed cell types. The majority of AIS are found in the transformation zone. AIS may be associated with CIN of the squamous epithelium in one- to two-thirds of cases.

figure 2.6: Adenocarcinoma in situ...

figure 2.6: Adenocarcinoma in situ...